This article provides all the information you need to understand and configure NAT on Cisco ASA and Cisco ASA-X Firewalls.

There are four possible methods of address translation, and each were defined in the Network Address Translation article series: Static NAT, Static PAT, Dynamic PAT, Dynamic NAT. This article assumes prior knowledge of each of these concepts. If you need a refresher, please check out the article series.

Cisco ASA NAT – Contents:

- Part 1 – NAT Syntax

- Objects

- Real and Mapped

- Auto NAT

- Manual NAT

- Part 2 – NAT Configuration Examples

- Static NAT

- Static PAT

- Dynamic PAT

- Dynamic NAT

- Part 3 – Advanced NAT

- Policy NAT

- Twice NAT

- NAT Precedence

- Identity NAT

- Summary

Part 1 – NAT Syntax

There are two sets of syntax available for configuring address translation on a Cisco ASA. These two methods are referred to as Auto NAT and Manual NAT. The syntax for both makes use of a construct known as an object. The configuration of objects involve the keywords real and mapped. In Part 1 of this article we will discuss all five of these terms.

Objects

An object is a construct which represents any single item in your network environment. Two types of objects can be configured:

- a network object — represents one IP address, or one IP Subnet, or one IP address range

- a service object — represents one set of a Protocol, Source Port, and/or Destination port

The idea is to configure and define an object, then reference that one item in your configuration by the object’s name.

Network Objects

To configure a network object, first use the following syntax to create the object:

Then define the content of the object as either a single IP Address, or a single IP Subnet, or a single IP Address range using either of the commands below:

Below are examples of each of the three types of network objects:

To create a network object which represents your web server’s IP address, you would use the following syntax:

To create a network object which represents your Inside network, you would use the following syntax:

Lastly, to create a network object which represents a particular IP address range, you would use the following syntax. This will define a range that includes all five IP addresses in the inclusive range of 72.6.6.10 through 72.6.6.14.

Service Objects

To configure a service object, first use the following syntax to create the object:

The content of the service object must include at least a protocol, and can also include a source port, destination port, or both. Here are examples of all four possibilities:

The specific port number the object represents can be identified using certain operators – the example above uses eq and gt. Five different operators exists:

eq <Port#> | Port must be equal to <Port#> |

gt <Port#> | Port must be greater than <Port#> (equal to <Port#> will not match) |

lt <Port#> | Port must be lesser than <Port#> (equal to <Port#> will not match) |

neq <Port#> | Port must be not equal to <Port#> |

range <Start#> <End#> | Port must be in the inclusive range of <Start#> to <End#> |

Viewing Objects

Two commands are available to view objects:

The show run object command lists the objects essentially as they were configured above:

And the show run object in-line command displays the same as above, except every object definition will be on the same line as the object name:

Using the in-line variant makes it much easier to “pipe include” and search for a specific object name and/or definition:

If you had done the “pipe include” without the in-line option you just would have received the full name of the object, but not the object’s definition.

Real and Mapped

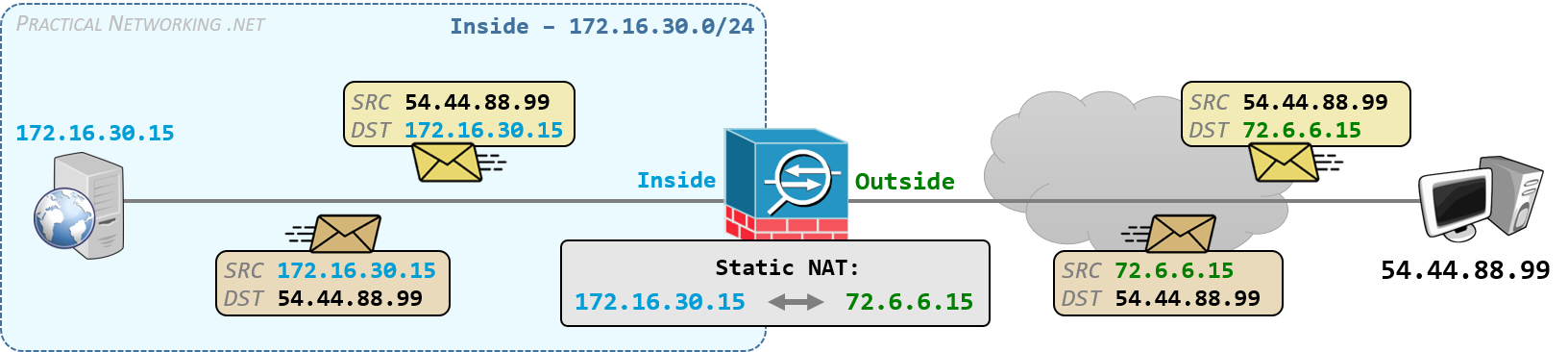

NAT configuration on the Cisco ASA will make use of the keywords real and mapped. These terms can be applied to IP addresses or interfaces. We will define these with the example of a Static NAT below:

The word real indicates what is really configured on a server.

For example, the web server at the IP address .15 is really configured with the IP address 172.16.30.15, which means the actual NIC really has the IP address 172.16.30.15 configured. Hence, 172.16.30.15 is considered the real IP address.

Moreover, the real IP exists on the ASA’s Inside interface. Hence, for the translation above, the Inside interface is considered the real interface.

The word mapped indicates attributes after a translation has occurred.

For example, the real address 172.16.30.15 is being translated to 72.6.6.15. Which makes 72.6.6.15 the mapped address. Moreover, the mapped address exists on the ASA’s Outside interface. Hence the Outside interface is considered the mapped interface.

Another way to remember it is the mapped attributes only exist because the ASA created them, whereas the real attributes exist despite any configuration on the ASA.

Auto NAT

We discussed the configuration of Objects because Auto NAT is configured within the Object definition, and we discussed the keywords Real and Mapped because the syntax uses these terms to designate the addresses involved in the translation.

With those items defined, we can finally discuss the definition and syntax of Auto NAT.

Auto NAT can be used anytime you need to make a NAT decision based upon only the Source of traffic. Which means each of the four types of translations (Static NAT, Static PAT, Dynamic PAT, Dynamic NAT) can be configured with Auto NAT.

Auto NAT Syntax

This is the syntax for Auto NAT is as follows (remember, this will be applied within the object definition):

nat | The configuration for Auto NAT starts with the nat command within an object definition |

<REAL-INTERFACE> | The interface on the ASA which faces the the <real-ip> (defined within the object) |

<MAPPED-INTERFACE> | The interface on the ASA which faces the <mapped-ip> |

<static|dynamic> | Use static for Static NAT or Static PAT, use dynamic for Dynamic NAT or Dynamic PAT |

<MAPPED-IP> | The IP address to which the object is being translated. This can be specified as an IP address directly or using the name of another object. You also have the option of specifying the interface keyword to use the IP address assigned to the mapped-interface |

Notice the elements of the syntax did not include specifying a <real-ip> – it is inherited from the object’s definition. Consequently, Auto NAT can only be configured directly within an object.

This is a complete example configuration of a Static NAT for the Web server from the image above. The real-IP 172.16.30.15 is being translated to the mapped-IP 72.6.6.15 when packets are traveling between the real-interface inside and the mapped-interface outside (and vice versa).

This is a complete example configuration of a Dynamic PAT for the Inside segment from the image above. The real-ip addresses in the 172.16.30.0/24 network are sharing the IP address of the mapped-interface outside.

Auto NAT with a Port Translation

The syntax above did not include the arguments necessary to allow you to map one port to another – namely, to configure a Static PAT.

In order to translate ports, you must add the service section to the end of your AutoNAT command. Giving us an updated syntax as follows (again, this is configured within an object):

service | indicates a translation of port numbers |

<tcp|udp> | specifying whether this translation affects TCP or UDP ports |

<REAL-PORT> | identifies the port number associated with the real IP address |

<MAPPED-PORT> | designates the port number associated with the mapped IP address |

There is no such thing as a “dynamic” explicit translation between ports, so a Static PAT translation will always use the static designation.

This is a complete example configuration of a Static PAT for the Web Server. The Web Server’s SSH port (TCP/22) is being hidden behind a non-standard port on the Outside (TCP/2222):

Notice, we had to create a new object – each object can only contain one translation, and we were already using the object WEB-SERVER for the Static NAT example above.

Manual NAT

There are two primary differences between Manual NAT and Auto NAT:

- Auto NAT can only make a NAT decision based upon the Source* of traffic.

- Auto NAT can only translate the Source* of traffic.

- Manual NAT can make a NAT decision based upon the Source, or upon both the Source and Destination.

- Manual NAT can translate the Source, the Destination, or even both the Source and Destination at the same time.

In short, Manual NAT can do everything that Auto NAT can, and a little extra – namely, Policy NAT and Twice NAT.

Of course, this doesn’t make Auto NAT obsolete. Instead, the “much simpler to configure” Auto NAT should be used whenever the additional features of Manual NAT are not needed.

Moreover, Auto NAT statements automatically sort themselves into a (generally) sensible order. Whereas the ordering of Manual NAT statements has to be manually considered. The details of this NAT precedence implication will be discussed later in this article.

The syntax of Manual NAT requires using objects for every reference to IP addresses and Ports. The configuration of objects was covered earlier in this article. You may also use object-groups, which are constructs that combine multiple objects together.

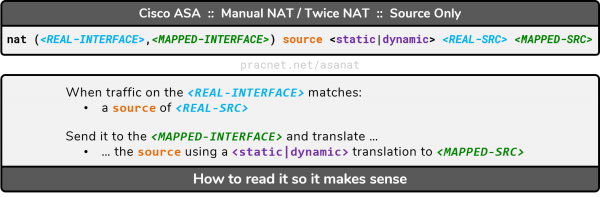

Manual NAT Syntax – Source Only

The syntax for Manual NAT statements which only affects the Source of traffic is as follows. Note that every term in italics below is the name of an Object which identifies a particular IP or set of IP Addresses:

The syntax is similar to Auto NAT, except for a key difference: Manual NAT is not configured within an Object — it is configured directly from global configuration mode (aka, configure terminal).

This is the definition of each argument in the Manual NAT syntax:

nat | All manual NAT statements start with the command nat |

<REAL-INTF> | The interface which faces the addresses contained in the object <REAL-SRC> |

<MAPPED-INTF> | The interface which faces the addresses contained in the object <MAPPED-SRC> |

source | Indicating the next three arguments are matching and translating the source of outbound traffic |

<static|dynamic> | Use static for Static NAT or Static PAT, use dynamic for Dynamic NAT or Dynamic PAT |

<REAL-SRC> | An object which defines the pre-translation IP Address(es) |

<MAPPED-SRC> | An object which defines the post-translation IP Address(es) |

The examples above of a Static NAT and Dynamic PAT with AutoNAT can be re-written using Manual NAT as follows:

Note that the Manual NAT statement is configured external of the Object definition. In addition, note that you can still use the interface keyword to designate using the IP address of the <MAPPED-INTF> for the <MAPPED-SRC>.

The Manual NAT statement above is the simplest form of the Manual NAT syntax. Later, we will add two more clauses to this statement: a clause that considers the destination and a clause that considers ports.

However, first we must understand how to read the Manual NAT statement in its simplest form. Use this technique to turn Manual NAT syntax into more human-readable language.

Every variation of the Manual NAT statement that follows will start with the exact syntax above. In each case, we will also expand the “how to read” section to simplify understanding what is being translated and how it is being translated.

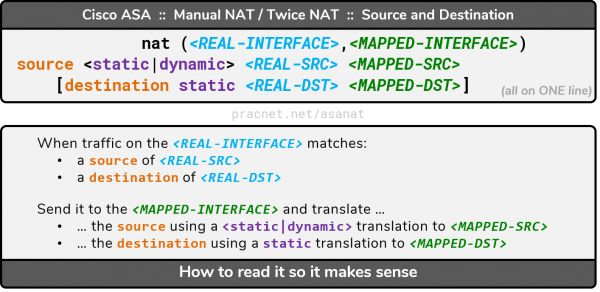

Manual NAT Syntax – Source and Destination

The syntax for Manual NAT that considers both the Source and Destination of traffic is as follows:

You’ll notice the syntax is identical to “source-only” Manual NAT in the preceding section. The only addition is this part at the end:

destination | Indicates the next three arguments are matching and/or translating the Destination of outbound traffic |

static | The destination of outbound traffic can only be translated explicitly – dynamic is not an option |

<REAL-DST> | An object which defines the pre-translation destination IP Address(es) |

<MAPPED-DST> | An object which defines the post-translation destination IP address(es) |

Later in this article, we will provide use cases for Manual NAT statements that include both the Source and the Destination. For now, we just want to thoroughly define the syntax and how to interpret Manual NAT statements.

We can extend the technique in the previous section which makes Manual NAT syntax more human-readable.

Notice, the translation will only occur if the traffic matches both the Source and Destination designated in the objects <REAL-SRC> and <REAL-DST>.

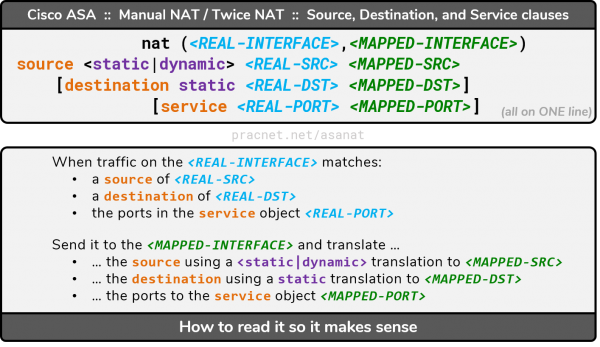

Manual NAT Syntax – Port Translations

The syntax for Manual NAT that involves translating TCP or UDP ports as well as IP Addresses is as follows:

This command is configured on one line. But for the sake of simplicity, we will present the same syntax with each clause on its own line:

You’ll notice the syntax is identical to “source and destination” Manual NAT in the preceding section. The only differences are that the destination clause is optional and the service clause is appended to the end:

service | Indicates this translation will also translate ports, i.e. this will be a PAT |

<REAL-PORT> | A service object which defines the pre-translation ports and protocols |

<MAPPED-PORT> | A service object which defines the post-translation ports and protocols |

Earlier we provided an example of a Static PAT using Auto NAT. We can create an identical translation using Manual NAT with the following code:

Recall, every reference to IP addresses or Ports in a Manual NAT statement must use an object.

Moreover, note that the service objects were defined specifying a source port. NAT statements are written from the perspective of outbound traffic (traveling from inside to outside).

In our Static PAT example, our goal was to translate destination port TCP/2222 on the outside to TCP/22 on the inside for inbound traffic. In the outbound packet the source port will change from TCP/2222 to TCP/22. Our NAT statement above simply matches the response traffic.

As before, we will extend the human-readable Manual NAT technique to include the service section (again, the command is all on one line, but each clause is listed on its own line below for simplicity):

Again, traffic will only be translated if all three designations of the real attributes match: <REAL-SRC>, <REAL-DST>, and <REAL-PORT>.

The infographic above represents the complete Manual NAT syntax and might make a handy cheat sheet or print out to simplify the configuration and interpretation of Manual NAT statements.

Part 2 – NAT Configuration Examples

In Part 1 of this article series, we discussed the syntax and use cases for Auto NAT and Manual NAT. In this section we will provide configuration examples for every type of address translation using both Auto NAT and Manual NAT on a Cisco ASA or Cisco ASAx Firewall.

In addition to the configuration commands, we will also list the output of the show nat, show run nat, and show run object commands for each entry below.

translation and un-translation counters will be zero. To simplify the output, these lines have been omitted.Static NAT

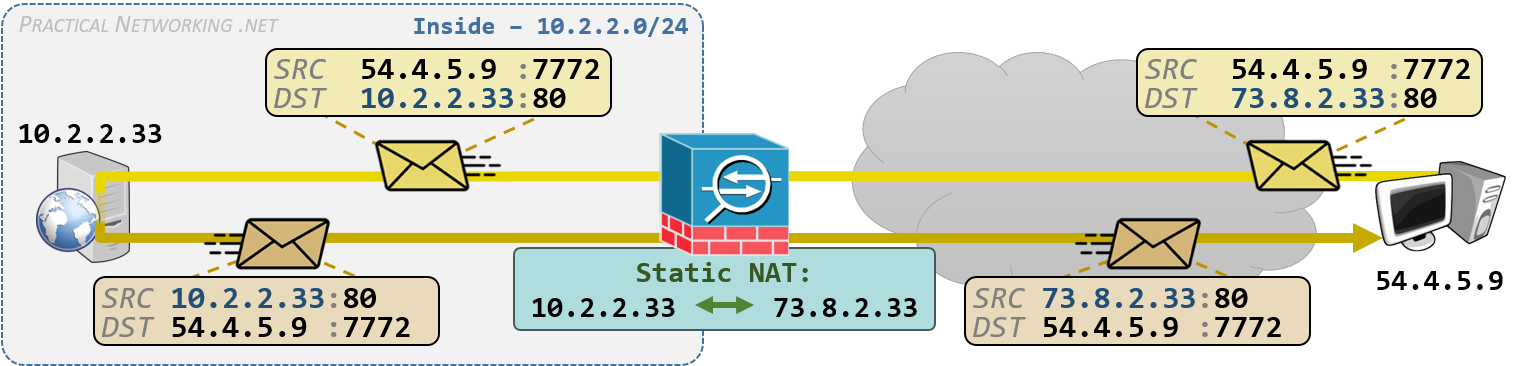

A Static NAT is a translation in which only the IP addresses are being modified, and the mapping between pre-translation and post-translation IP addresses is explicitly defined.

This is the illustration of a Static NAT from the NAT article series:

Static NAT can be configured using Auto NAT or Manual NAT.

Static NAT with Auto NAT

Static NAT with Manual NAT

The choice between using Auto NAT or Manual NAT to configure Static NAT has to do with NAT order of operations – this will be discussed in the NAT Precedence section.

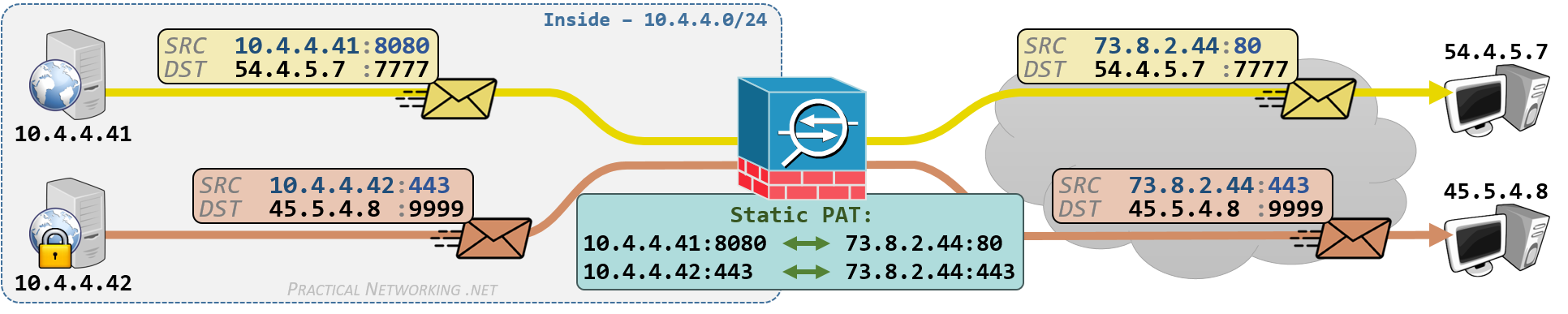

Static PAT

A Static PAT is a translation in which the IP Addresses and Port numbers are being modified, and the mapping between pre-translation and post-translation attributes is explicitly defined.

This is the illustration of a Static PAT from the NAT article series. Click the tabs to view the Inbound or Outbound flow:

Static PAT with Auto NAT

Static PAT with Manual NAT

Notice, for the second translation we are reusing the object TCP443 to indicate a translation to the same port — in essence, not translating the port, but still creating a “channel” through 73.8.2.44 on port 443.

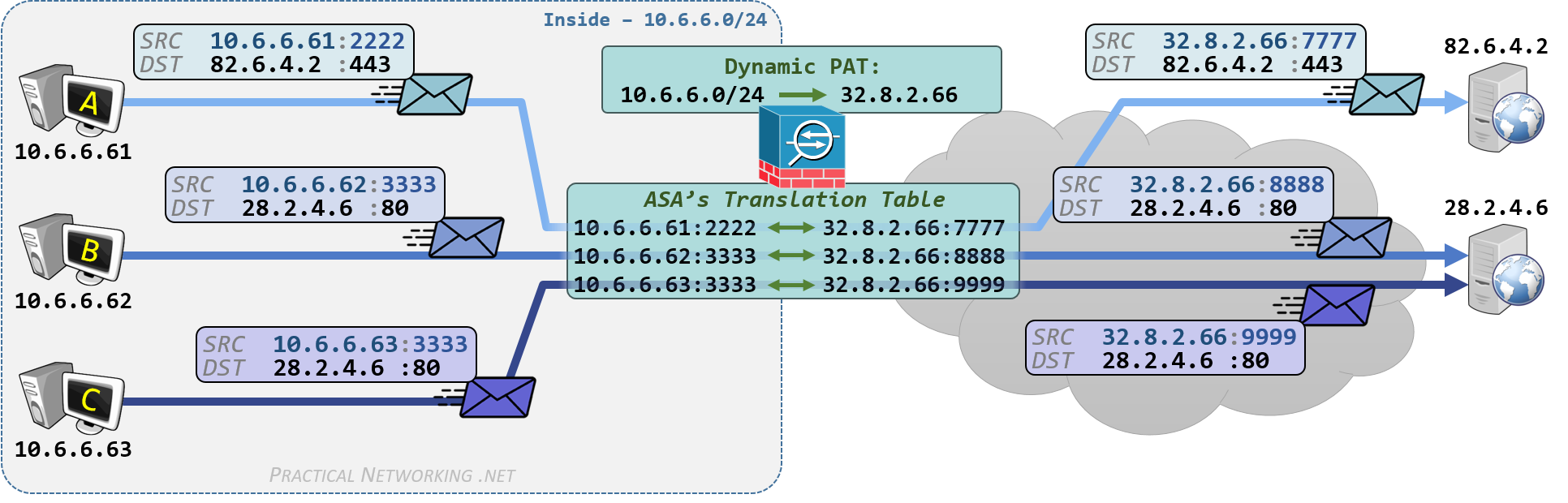

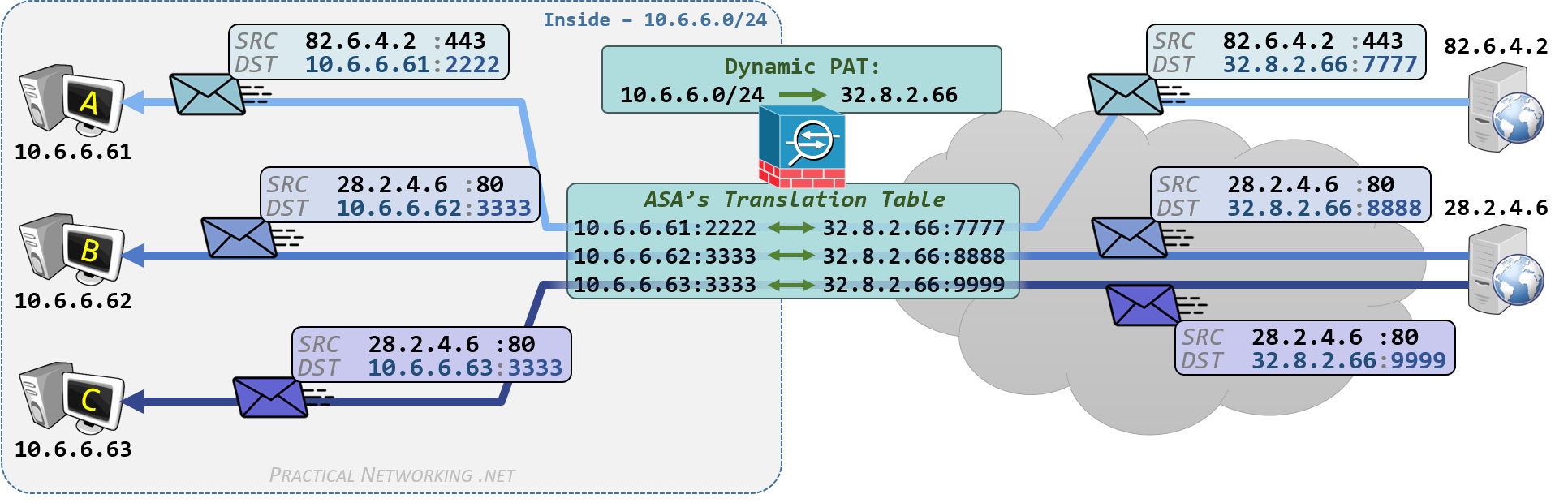

Dynamic PAT

A Dynamic PAT is a translation in which the IP addresses and Port numbers are being modified, and the mapping between pre-translation and post-translation attributes is dynamically determined by the Firewall.

Said another way, a Dynamic PAT allows multiple internal hosts with Private IP addresses to share one (or more) Public IP addresses.

This is the illustration of a Dynamic PAT from the NAT article series. Click the tabs to view the Outbound or Inbound flow.

Dynamic PAT with Auto NAT

Dynamic PAT with Manual NAT

The choice between using Auto NAT or Manual NAT to configure Dynamic PAT has to do with NAT order of operations – we will discuss this in the NAT Precedence section.

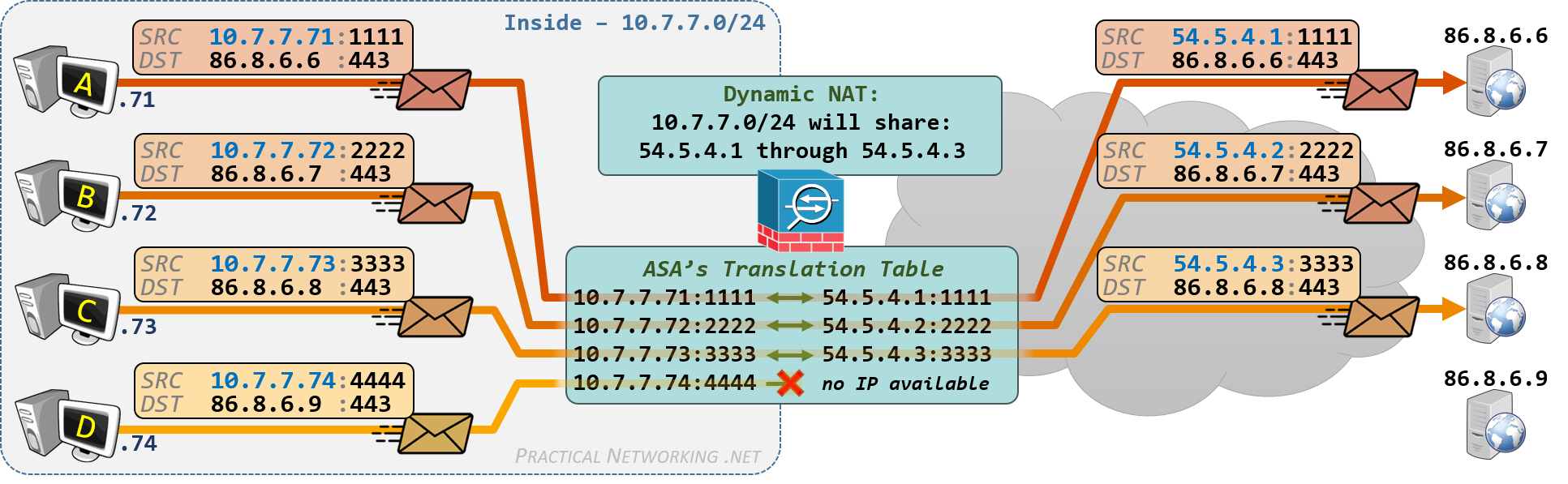

Dynamic NAT

A Dynamic NAT is a translation in which only the IP addresses are being modified, and the mapping between pre-translation and post-translation IP addresses is dynamically determined by the Firewall.

Said another way, a Dynamic NAT allows multiple internal hosts with Private IP addresses to temporarily own a dedicated Public IP address so long as they have an active session.

This is the illustration of the Dynamic NAT from the NAT article series:

Dynamic NAT with Auto NAT

Looking at the configuration above, it might appear to be identical to the Dynamic PAT configuration in the preceding section. There is, however, a key difference:

To configure a Dynamic NAT, you must designate the mapped-IP address using an object defined with a range of addresses. If you use an IP address directly, or an object defined with host or subnet, the ASA will perform a Dynamic PAT.

You also have the option to configure the Dynamic NAT as you did above, while designating that all remaining hosts can share an interface IP address – this is known as configuring a fallback IP address.

To configure the Interface IP as a fallback, simply append the argument interface to the Dynamic NAT command:

Dynamic NAT with Manual NAT

Just like in the preceding Auto NAT configuration, the fact that the mapped-IP is a network object defined with a range makes this a Dynamic NAT (instead of a Dynamic PAT).

The same option exists to use the Interface IP of the Mapped interface as the Dynamic PAT fallback option:

The choice between using Auto NAT or Manual NAT to configure Dynamic NAT has to do with NAT order of operations – this will be discussed in the NAT Precedence section.

Part 3 – Advanced NAT

In Part 1, we explored the syntax of configuring Objects, the terms Real and Mapped, the syntax of Auto NAT, and the syntax of Manual NAT.

In Part 2, we provided configuration examples on a Cisco ASA firewall for each type of address translation: Static NAT, Static PAT, Dynamic PAT, Dynamic NAT.

In Part 3, we will continue our exploration of Network Address Translation on a Cisco ASA or Cisco ASA-X Firewall by looking at some advanced concepts.

Namely, we will define and look at configuration examples for Policy NAT and Twice NAT, then discuss the concept of Identity NAT, and finally explain the NAT order of operation on a Cisco ASA or Cisco ASA-X Firewall by looking at some advanced concepts.

Namely, we will define and look at configuration examples for Policy NAT and Twice NAT, then discuss the concept of Identity NAT, and finally explain the NAT order of operation on a Cisco ASA or Cisco ASA-X Firewall.

Policy NAT

Each of the four types of translations we illustrated above involved making a NAT decision based upon only matching the source of incoming traffic. This causes all traffic from a particular source to be translated the same way.

There are times when it might be beneficial to conditionally translate traffic based upon its destination. In those cases, you are performing what is known as a Policy NAT.

A Policy NAT is any of the four types of address translation we have already discussed (Static NAT, Static PAT, Dynamic PAT, Dynamic NAT), except the translation decision is based upon both the Source and the Destination.

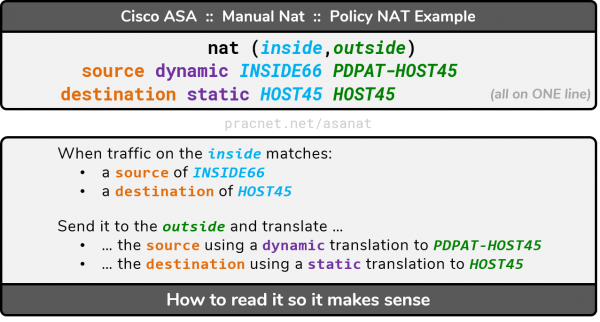

To configure a Policy NAT on a Cisco ASA, you would use the Manual NAT syntax which includes the Source and Destination clauses. A Policy NAT cannot be configured using Auto NAT syntax — Auto NAT only considers the Source.

We will provide a Policy NAT configuration example using the following scenario:

The configuration in the illustration above involves two parts: A Policy Dynamic PAT and a regular Dynamic PAT. The regular Dynamic PAT is the same one that we showed in the Dynamic PAT example above – those commands have already been provided and won’t be repeated below.

The commands for the Policy Dynamic PAT are as follows:

If we apply what we learned in the human-readable technique for Manual NAT statement to the commands above, we can infer exactly what is happening:

Essentially, the source is being dynamically translated from INSIDE66 to PDPAT-HOST45, and the destination is being statically translated from HOST45 to HOST45 as the traffic traverses from inside to outside.

In all cases, the real attributes are being translated to their mapped counterparts.

The destination is being translated to itself – in other words, not being translated. We’ll expand on this type of “translation” later in this article.

The effect of the configuration above makes it so when the Inside network (10.6.6.0/24) is speaking to the IP 45.5.4.9, the traffic will be translated using Dynamic PAT to 32.8.2.77. If the traffic from the Inside network is not going to the 45.5.4.9 IP address, the regular Dynamic PAT configuration would continue to translate the packet to 32.8.2.66.

Note, since the above configuration involves two separate configuration items that work together, we must consider the order in which the NAT statements are processed. We will explore these considerations in the NAT Precedence section that follows.

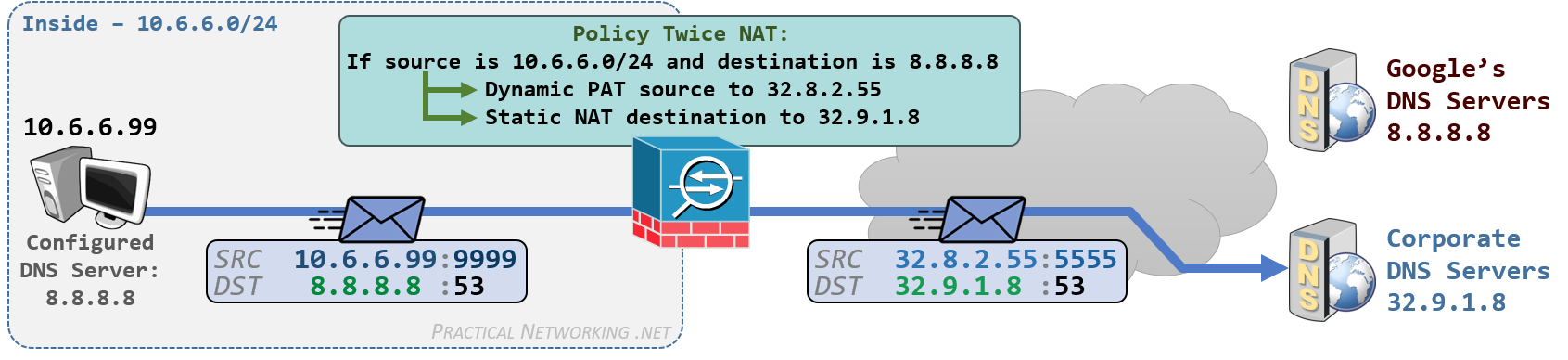

Twice NAT

The Policy NAT in the preceding section provided an example of translating the source, based upon matching the source and destination. Note that only the source was translated.

There are times when it is beneficial to translate both the source and destination – in those cases you would use what is called a Twice NAT – i.e, performing NAT two times: once on the source and once on the destination.

The configuration for a Twice NAT is very similar to the Policy NAT above. We will use the scenario below:

The scenario for the image above is explained in the Twice NAT article from which it was taken:

10.6.6.0/24) that have chosen to use Google’s Public DNS Resolving Server (8.8.8.8). However, company policy states DNS requests must be made using the Corporate DNS server (32.9.1.8). One option is … to translate any outbound requests to 8.8.8.8 into a request for 32.9.1.8.Notice the configuration of a Twice NAT also involves a Policy NAT. The Policy NAT portion will match DNS traffic from the Inside network destined to 8.8.8.8, and the Twice NAT portion will translate the source using Dynamic PAT and the destination using Static NAT.

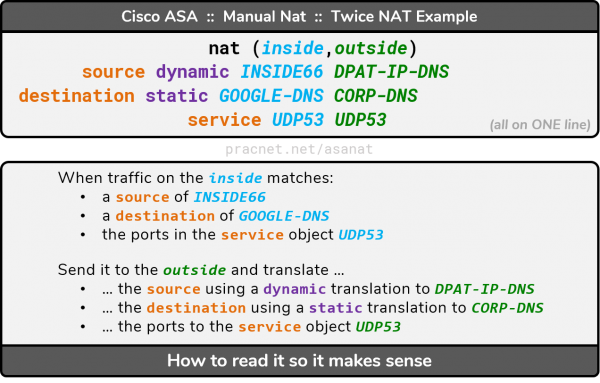

Since we only want this rule to match on DNS traffic, we will use the syntax of Manual NAT which includes the service section.

Notice the service object definition uses destination UDP/53 in this case. DNS traffic leaving the Inside network will have a protocol of UDP and a destination port of 53 – this is the outbound traffic we are intending to match.

We can apply our technique to make the Manual NAT statement human-readable to easily interpret what is occurring:

Essentially, the source is being dynamically translated from INSIDE66 to DPAT-IP-DNS, and the destination is being statically translated from GOOGLE-DNS to CORP-DNS if the traffic matches the ports specified by UDP53, which will also be “translated” to UDP53.

In all cases, the real attributes are being translated to their mapped counterparts. The order of the items in the manual NAT statement remains constant: Always real, then mapped.

To summarize four different concepts are collaborating in the illustration and configuration example above:

- We are making a decision based upon the source and destination, which makes it a Policy NAT.

- Both the source and destination of traffic are being translated — this is, by definition, a Twice NAT.

- The source is being translated with a Dynamic PAT

- The destination is being translated with a Static NAT.

NAT Precedence

The ASA processes address translation statements in a very specific order. You must understand this order, along with the configuration syntax outlined above, to truly become a master of address translation on the Cisco ASA and Cisco ASA-X Firewalls.

The core of how it works is as follows:

Every Manual NAT statement takes precedence over every Auto NAT statement. However, there is a way to de-prioritize specific Manual NAT statements to occur after the Auto NAT statements.

This creates three sections that all NAT statements fall into – which constitute the NAT order of operation:

- Section 1: All Manual NAT Statements

- Section 2: All Auto NAT Statements

- Section 3: All Manual NAT Statements de-prioritized to occur after Auto-NAT

You may have seen Section 1 and Section 2 in the output from the show nat command above.

The idea behind the three sections is that since Manual NAT statements have the option of making decisions on Source and Destination, they tend to be more specific than Auto NATs (which can only make a decision based on source). As a result, Manual NAT statements should have higher priority than Auto NAT statements.

However, there might be times when you want to use a Manual NAT statement for a generic translation (maybe one that only makes a decision on the Source), but have it apply after more specific Auto NAT statements.

We will illustrate this using the same image we used for Policy NAT earlier, but we will add two additional Static NAT translations for Host A and Host B (these translations are not depicted on the image):

First, let’s create all the objects we will need:

Then we will create four translation statements using the newly created objects:

- A Policy NAT so traffic from the Inside to

45.5.4.9will be translated using Dynamic PAT to32.8.2.77 - A Static NAT for Host A to translate

10.6.6.61to32.8.2.61 - A Static NAT for Host B to translate

10.6.6.62to32.8.2.62 - A Dynamic PAT for the remaining traffic from the Inside network using Manual NAT syntax using the IP

32.8.2.66

Notice, the final Manual NAT statement includes the keyword after-auto. This is what “de-prioritizes” the statement, causing it to occur after the Auto NAT statements.

We can see the exact order in which NAT will occur using the show nat statement. Once again, since this output is from a lab device, the translate and untranslated hits will be 0, so those lines have been excluded:

With the output from the show nat command, we see very clearly the three sections. Section 1 included our Policy NAT applied with Manual NAT syntax. Section 2 included both our Static NAT statements applied with Auto NAT. Section 3 included any Manual NAT statement applied with the after-auto keyword.

Had we not used the after-auto keyword for our Dynamic PAT, it would have appeared in Section 1. If that was the case, the Dynamic PAT statement would have taken precedence over the Static NAT statements (in Section 2) and all traffic from Host A and Host B would be translated to 32.8.2.66, instead of their dedicated Static NAT IP addresses.

Using the after-auto keyword, however, allowed the generic Dynamic PAT statement to occur after Section 2, allowing Host A and B to use their dedicated Static NAT addresses. And Host C/D/E (etc… — not pictured) would use the generic Dynamic PAT statement in Section 3 to speak through the Firewall.

And of course, in all cases, the very specific Policy Dynamic PAT occurring in Section 1 will always take precedence over the other translations.

The example above describes the three sections of NAT precedence on Cisco ASA and Cisco ASA-X Firewalls. But within each Section there is also an order of NAT operations to consider.

NAT Precedence within the Manual NAT Sections

Both Section 1 and Section 3 include Manual NAT statements. The priority within either of these sections is determined by the order they appear in the configuration.

To help control this, each statement receives an incrementing line number automatically. Take a look at this example:

When this configuration is applied (assuming the mock objects AAA–FFF have been created), we would see this in the show nat output:

Notice, the first statement was placed at Line 1, the second at Line 2, and the third at Line 3 – they simply followed the order they were configured.

Had we used the after-auto keyword for each statement, they would have appeared as Lines 1, 2, and 3 of Section 3.

We can insert a Manual NAT statement at a specific line number by simply specifying the desired line number. The syntax is as follows:

Notice the location of the optional [after-auto] keyword, and the [Line Number] occur directly after specifying the real and mapped interfaces in parenthesis. Once again, the line number denotes the NAT Precedence within either Section 1 or Section 3 – the two Manual NAT sections.

Using the line number, we can specify a particular Manual NAT statement to occur at Line 2:

We can verify the effect using show nat:

The new line was inserted at line 2. And all the other Manual NAT statements simply shifted down: the original Line 2 became Line 3, and the original Line 3 became line 4.

NAT Precedence within the Auto NAT Section

NAT precedence within the Auto NAT section comes down to four rules. We will provide examples of each rule by configuring these five Auto NAT statements:

- A Dynamic PAT for the

10.9.9.0/24network to the IP72.9.9.24 - A Dynamic PAT for the

10.9.9.48/29network to the IP72.9.9.29 - A Static NAT for the Web Server at

10.9.9.80to72.9.9.80 - A Static NAT for the Database Server at

10.9.9.33to72.9.9.33 - A Static PAT for the Database Server so

10.9.9.33:22maps to72.9.9.33:2222

The configuration is applied with these commands, in this order:

Notice, these are all Auto NAT statements, which means they will all appear in Section 2. We will look at the output of the show nat detail command to see exactly what is being translated. And again we will exclude the lines which include all the translate hits and untranslated hits:

The first thing to notice is all three static translations (line 1,2,3) took higher priority than both dynamic translations (line 4 and 5). This brings us to the first rule of precedence within Auto NAT: Rule #1 is static translations always take higher priority than dynamic translations.

Next, if you look at the dynamic translations (line 4 and 5), the one translating the /29 network took higher priority than the one translating the /24 network. Which brings us to Rule #2, more specific translations take precedence over less specific translations (based on the Real IP). A /29 includes eight IP addresses and a /24 includes 256, which makes the /29 more specific.

All three static translations (line 1,2,3) specify a single Real IP, so they tie on Rule #2. What determines the order for these is simply the fact that the IP address 10.9.9.33 is numerically lower than 10.9.9.80. Rule #3 is that numerically lower Real IP take precedence over numerically higher Real IP.

And finally, take a look at line 1 and 2. Both of them are static translations, both of them have the same specificity (one IP), both of them have the same Real IP (10.9.9.33). Line 1 and 2 tie on all three rules we’ve covered so far.

The final rule, which will arbitrarily break any remaining ties is Rule #4, alphabetically based on object’s name. The name DB-SERVER is alphabetically before the name DB-SERVER-SSH – hence, the Static NAT is taking precedence over the Static PAT (which is typically undesirable – we’ll explore that in the next section).

So to summarize, the four rules for NAT Precedence within Section 2 – the Auto NAT section – are as follows:

- Static takes precedence over Dynamic

- Most Specific Real IP

- Numerically by Real IP

- Alphabetically by Object Name

Auto NAT Port Translations and NAT Precedence

If you look at the output from the example above, you will notice the Static NAT took precedence over the Static PAT.

This means if the Firewall receives a packet on the Outside interface destined to the IP address 72.9.9.33 and the TCP port 2222, it would be translated to the IP 10.9.9.33 and the port would remain TCP/2222. This is not ideal because we intended for traffic on port 2222 to be redirected internally to port 22.

Unfortunately, because of how Precedence works in Section 2, since both translations are static, and both specify a single address, and both translate the same Real IP, the only rule left which breaks ties is Rule #4: Alphabetically based on Object name.

To that end, it is a good idea to have a consistent structure for how you name your Static NAT and Static PAT statements using Auto NAT syntax to facilitate the PAT taking precedence over the NAT.

The Alphabetic priority is determined by the ASCII character codes. This means if you tend to name objects using words and numbers (A-Z, a-z, 0-9) that the following special characters alphabetically precede any letter or number: ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / . Of these characters, the slash and the comma are not eligible for Object Names. This means any of the following will always precede any letters or words: ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + - .

Applying that knowledge to the Auto NAT configuration above leads us to the following practical application of a Static PAT and a Static NAT:

We can verify the NAT precedence using show nat:

Notice, the Auto NAT rule within the object name +DB-SERVER took precedence over the AutoNAT rule within the object name DB-SERVER. This successfully prioritizes the Static PAT over the Static NAT within Section 2.

Identity NAT

Throughout this article we have had a few examples of Identity NAT but have not formally referred to them as such. This was intentional because the term Identity NAT sounds more complicated than it really is.

Identity NAT is nothing more than translating addresses to themselves. The end effect of which is essentially not translating certain traffic.

For example, when we provided a configuration example of a Policy NAT, we used the following syntax:

Notice the Real Destination and the Mapped Destination used the same object name (HOST45). We were translating the object HOST45 to the object HOST45 – translating it to itself, i.e. not translating it. This was an example of an Identity NAT.

Specifically, we performed a Dynamic PAT on the source, and an Identity NAT on the destination.

The configuration of Identity NAT simply involves re-using an object as both the real object and the mapped object.

NAT Exemption on a Cisco ASA or Cisco ASA-X Firewall

Identity NAT is how you configure what is known as NAT Exemption – the concept of designating certain traffic to be exempt from address translation. Or said another way, designating certain traffic to not be translated.

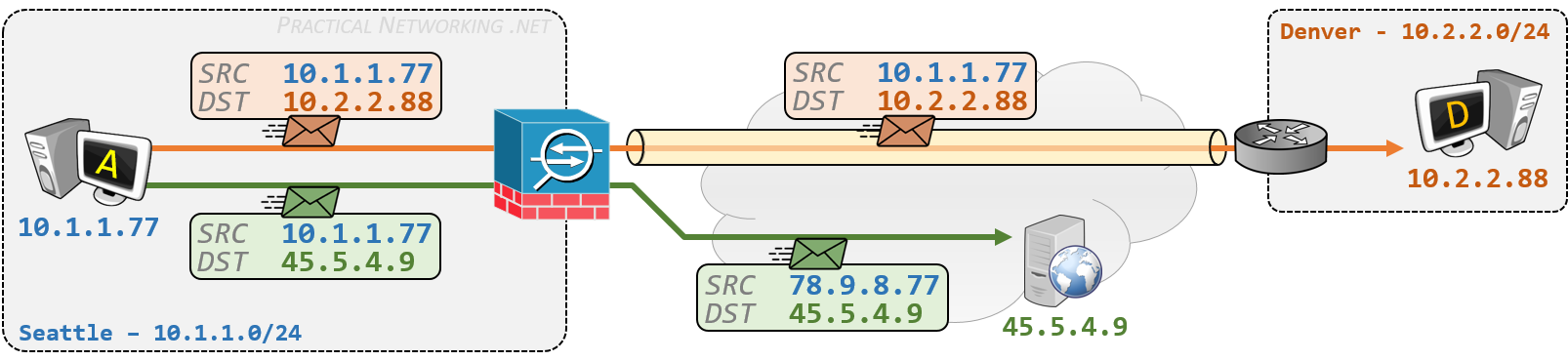

For example, below is an ASA configured with a generic Dynamic PAT which translates the entire Seattle network (10.1.1.0/24) to the IP 72.3.3.77 when speaking to the Internet.

However, the ASA also has a VPN tunnel built to the Denver site. We want traffic from Seattle (10.1.1.0/24) to Denver (10.2.2.0/24) to be exempted from the generic Dynamic PAT so these two sites can speak to each other directly using private IP addresses.

In such cases, you would configure a NAT Exemption on the ASA for traffic from 10.1.1.0/24 to 10.2.2.0/24. As mentioned before, the NAT Exemption configuration involves configuring an Identity NAT, i.e. translating traffic to itself:

With the configuration above, the Manual NAT statement would appear in Section 1 and take precedence over the Auto NAT statement which would appear in Section 2:

Traffic from Seattle to Denver would match the Manual NAT statement and not be translated (Identity NAT), and traffic from Seattle to anywhere else on the Internet would match the Auto NAT statement and be translated using Dynamic PAT to 72.3.3.77.

Cisco ASA NAT – Summary

The Cisco ASA and Cisco ASA-X firewalls provides nearly infinite flexibility in so far as their NAT configuration. From the modularity of using objects, to the simplicity of configuring Auto NAT, to the granularity of Manual NAT, to the precision of NAT precedence — the ASA can do it all.

This article covers each of these concepts in detail, explaining what they mean, when to use them, and how to apply them. If you read it from start to finish, and were able to follow with the examples and illustrations, then you can decidedly consider yourself an address translation expert on the Cisco ASA platform.